Training Load 3

It has been about a year since I have attended the Tim Gabbett Seminar, and a lot has changed. Tim’s research has been called out (here) for some errors/misreporting of data, and I have gotten a chance to apply what I had learned with hundreds of clients and myself!

With the flaws pointed out in Tim Gabbett’s work, we can no longer use the acute-chronic workload ratio to predict injury risk. I still feel the two big take-aways from this seminar hold true, but just on more of an individual basis than we previously thought.

I think the concept that holds the most merit (and wasn’t directly called out in the piece above) is the part we discussed in part 1; and that is the idea that “training harder is training smarter.” This idea that higher chronic workloads are protective of injury and not the cause of injury is a mindset change that the strength and conditioning world needs to embrace. Tim Gabbett pushes this idea, which is becoming ever prevalent in the Physical Therapy world, that we are not machines but rather organic beings capable of adapting to the stressors placed on it. We need to scream this message from the rooftops. Strength coaches need to catch on and stop making people think they are capable of less than what they really are. We need to switch the narrative and show people all the amazing things they are capable of!

The workload-injury aetiology model

We also looked at the workload aetiology model and how there are two reasons that high chronic workloads were protective against injury. Those two reasons were high chronic workloads allowed an athlete to handle more load on any given week, and a higher chronic workload will allow for more training leading to a greater increase in strength and aerobic fitness, which are two modifiable risk factors for injury.

To further understand the idea that high chronic workloads are protective against injury, Gabbett uses the beer-drinking analogy. If you go out to a party and have ten drinks when you don’t drink that often you will likely blackout; but if you regularly drank ten drinks every day, then this would likely be no big deal. I am NOT telling you to go start drinking ten beers every day! The same goes for training if you are highly trained and constantly training at a high level you will be able to handle pretty much any physical stressor that comes your way!

Tim Gabbett’s research was still huge in showing us that we are capable of handling a lot more stress than we previously thought. Not only that we can handle it, but that the stress will make us stronger and more resilient.

In part 2, we looked at the concept of acute-chronic workload. This was the concept that was called out to be flawed, and because of that, I think there are a few important things to note. First, because of the variability in the data, we cannot say that a certain ACWR puts someone at a greater risk of injury. Secondly, this also does not mean ACWR is useless.

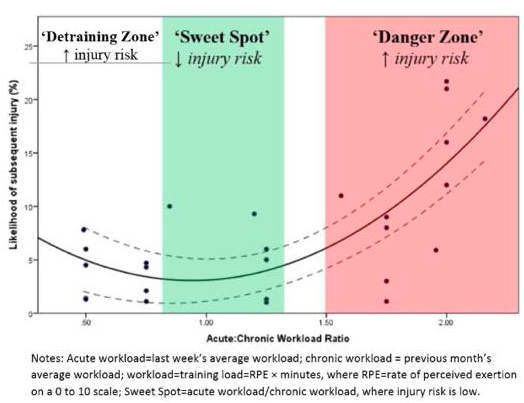

In the request to remove some of the acute-chronic workload data, there was a much greater variance in ACWR seen than what was reported. Because of that, the graph below is no longer significant!

Image from:

I think it is very important to note that no single ACWR is more indicative of injury than another. It is seen that people with ACWR all over the place get injured and the data was manipulated to show this trend. What we can still use from ACWR is to compare training load week to week. This utilized with other metrics can be used in a variety of ways. The image above can end up doing more damage than good especially if the athlete is aware of their ACWR. When an athlete’s acute-chronic workload spikes, they may nocebo themselves into a greater risk for injury even though the data does not support this idea. So just because your ACWR is high does not mean you are at a greater risk for injury!

You can still use workload and the ACWR to help monitor the stress placed on the athlete. This is particularly important when analyzing if a certain training block was effective. If the successive weeks of a training block were particularly productive, you might want to keep the overall stress of the next week the same and see how long you can ride that progress out before having to progress. By making sure your ACWR is as close to one as possible from week to week, you can be sure you are applying a similar amount of stress each week. Furthermore, if you find progress is stalling or not happening as quickly as you expected, you can measure how far you are pushing your athlete by how high your ACWR gets above 1.0. In practice, you will want to make the smallest increases as possible to keep progress rolling. ACWR allows us to measure that push in stress.

If your athlete can go weeks on end (usually over 6-8 weeks) without needing a deload or accumulating a significant amount of fatigue, then your overall training stress is probably too low and you can use the ACWR to progress your training slowly. Conversely, if you find your athlete progress is going backward or stalling out after just a few weeks of training, you may be doing too much and want to drop the ACWR.

Next, the ACWR still gives us a good idea of whether a current week or day of training is putting more stress on the body or driving recovery. This is particularly useful in analyzing the effectiveness of deload weeks or pivot blocks. During a pivot block or deload week, our main goal is to dissipate fatigue while maintaining strength, but how do we know if the week was effective?And how do we measure the difference in stress so that the results are repeatable? The answer is ACWR.

At the end of a pivot block or deload, you would like to see your athlete hit the same numbers or higher than they were hitting going into that deload and pivot block, but this does not happen very often. Sometimes the training is too easy, and the athlete comes back feeling lethargic and detrained. Sometimes, the training is too hard, and the athlete was not able to adequately recover. If you find that you hit the deload perfectly, take a look at the ACWR of that week and try to mimic it every deload. If you are finding that your athletes are looking lethargic and detrained, you probably dropped the overall stress too much and will want a higher ACWR. If you are finding your athletes are still feeling fatigued after the deload, then there was too much stress, and you should aim for a lower ACWR.

Although there were some flaws in Tim Gabbett’s research, the overall ideas still hold. Session RPE and time are factors that exist regardless of whether or not we track them, so we might as well track them because what gets measured gets managed!

Written By: Paul Milano