Training Load

This past weekend I had the honor of attending Tim Gabbett’s load management course. Tim Gabbett is one of the leading researchers when it comes to load and load management. There is a lot of talk about load management in the physical therapy world, but I haven’t seen too much talk in the strength and conditioning world about this research.

I feel that this research is just as important if not more important for a strength coach as these concepts allow us to progressively overload our athletes in the most efficient and safe manner. Progressive overload is a key concept when it comes to programming and has been shown repeatedly to be crucial to reaching our goals, but until now, there has been no way to measure this overload. Tim Gabbett’s research has given us some direction in how to optimally overload our athletes. You always hear the first rule as a strength coach is to do no harm and that means putting our athletes at little risk for injury as possible. Workload management should be the foundation of this.

But Paul, when you say load management, what exactly do you mean. To understand load management let’s look at the concept of load. Gabbett defines load as having two parts; external load and internal load. The external load is the act of performing work in preparation for or carrying out an event. For example, total workout time, miles traveled, number of jumps, weight you lift, etc. The easiest way to track this is total workout time. The internal load is the physiological, psychological, or biomechanical response to performing that work. We measure this through session RPE. To get the total load of each session you would multiply the internal load x the external load. In our case we would take Session Time x Session RPE to get a number for load. This will be a unitless number.

When calculating load, you can look at the short term and the long term. When looking at the load endured over a short period, from one day to one week, we refer to this as the acute workload. We can also look at load over a more long-term period. When doing this we refer to it as chronic workload. Because the acute workload is over a short period, we can say it is a measure of fatigue and because chronic workload is over a longer period it represents the load we are prepared to take or as a marker of fitness. We can also make a ratio of the acute vs. the chronic workload which we will discuss in part two of this article.

For me, there were two big takeaways from this seminar that we will be looking at in this series. In part one we will look at the concept of training harder is training smarter. The second, which we will look at in part two, is the concept that the load is not the problem but how well we are prepared for that load that will determine our injury risk.

First, we will look at the claim that the training harder is training smarter. To start, we will look at the current model for cause of injury; the workload-injury aetiology model.

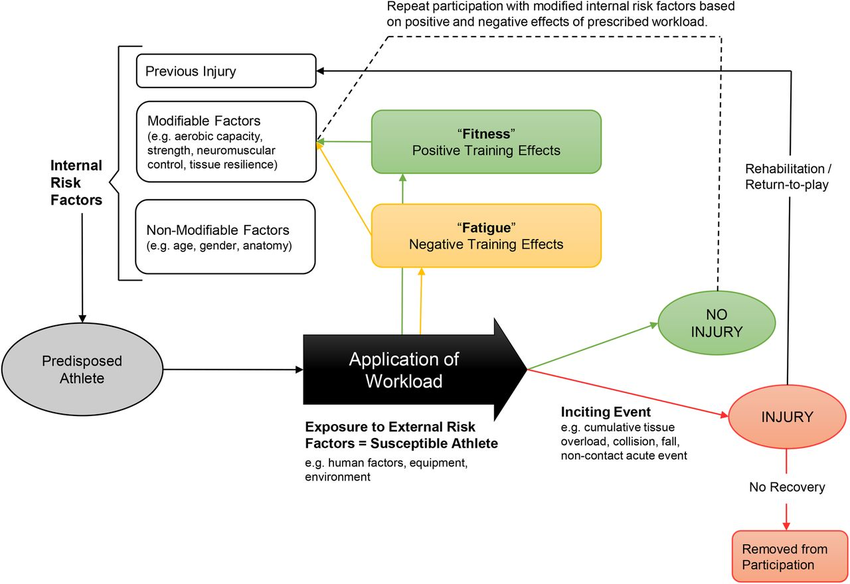

The workload-injury aetiology model

Image from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/305341467/figure/fig1/AS:385248446697474@1468861795410/The-workload--injury-aetiology-model.png

From this model, we can see that the application of workload can drive an athlete to or from an injury. We also see that load can drive fitness and fatigue which can positively or negatively affect the internal risk factors that make an athlete more or less resilient.

Previously we looked at how chronic workload is indicative of the load the athlete is prepared to handle or the athlete’s fitness. The idea that training harder is training smarter is simply saying the higher our chronic workload, the less likely we are to get injured for two reasons. First, the higher the chronic workload, the more load, the athlete, is prepared to handle. This means you can throw some crazy workouts at this athlete without spiking their workload. Workload spikes are something you want to avoid that we will go over in more detail in part two of this article.

Second, higher levels of chronic workload will drive fitness, which will have a positive effect on the athlete’s internal risk factors. An athlete who is stronger and more aerobically fit is at less risk for an injury and the higher we can drive the chronic workload the stronger and more aerobically fit we can make our athletes. We will take a closer look at these modifiable risk factors in part two.

This idea goes against the old train of thought that if you do too much, you will get worn down and injured. Tim Gabbett has done serval studies to back up this theory.

Study: Gabbett. (2018). Debunking the myths about training load, injury, and performance: Empirical evidence, hot topics, and recommendations for practitioners. Br. J. Sports. Med. In press.

In this study, you can clearly see the higher the chronic workload, the less chance for injury. The next study looks at the risk for high velocity sprinting and leads as a nice transition into part two of our series!

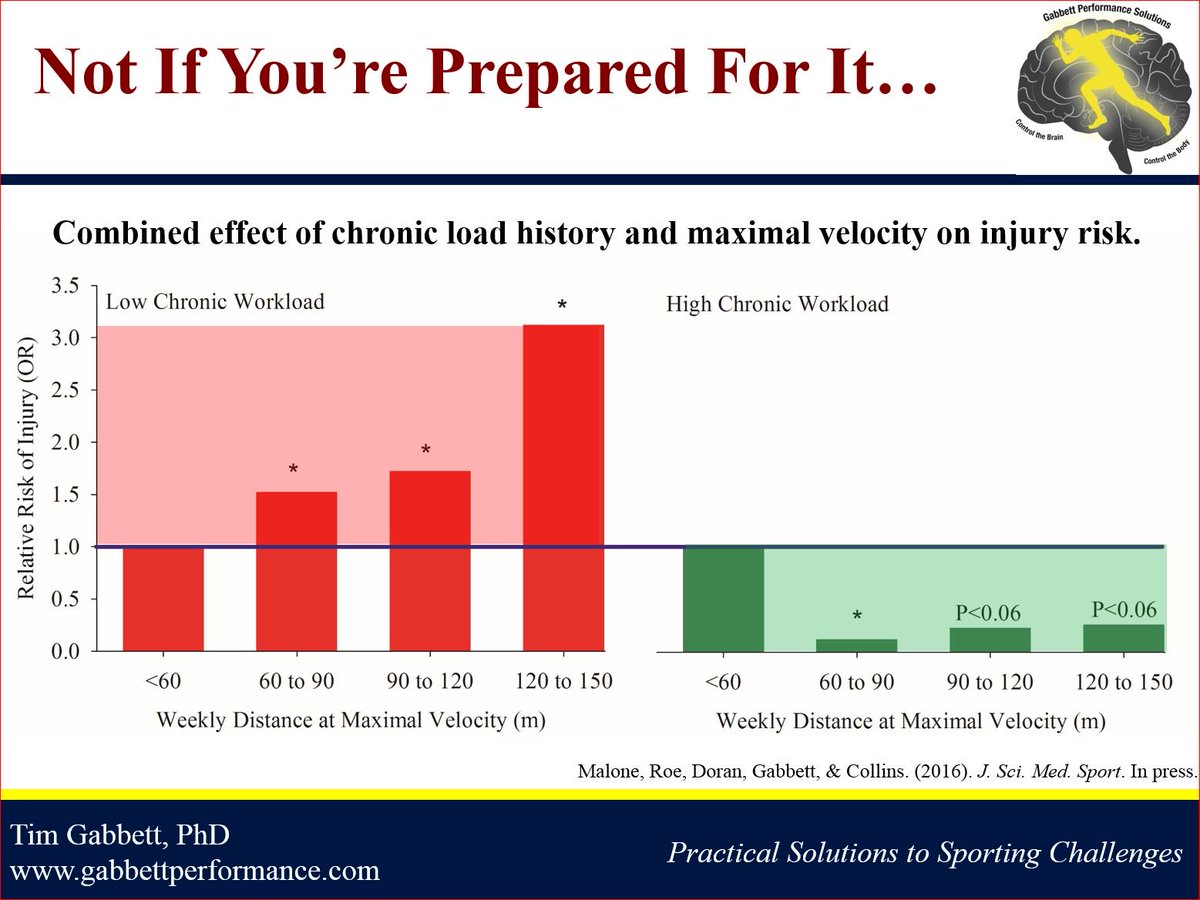

Image from Tim Gabbett’s twitter: https://pbs.twimg.com/media/Cq3HJovUAAAudFN.jpg

Study: Malone, Roe, Doran, Gabbett, & Collins. (2016). J. Sci. Med. Sport. In press

In this study, we can see the protective nature of having a high chronic workload as well as the danger of doing too much too soon. We have a high-intensity activity in sprinting, and we see that when chronic workload is high the athlete can handle almost endless amounts of sprinting, but when chronic workload is low these very same loads put the athlete at a greatly increased risk for injury. This highlights our second concept perfectly; the load is not the problem, but how you are prepared for that load. This concept we will dive into deeper next week in part two along with looking at how your lifestyle can affect all of this along with some practical application to your coaching or training. Stay tuned next week for another good one.

Written By: Paul Milano